I was born right after World War II into an aristocratic family. After the revolution, the Bolsheviks took away our country home and we moved into a communal apartment in Moscow.

My parents took up jobs at factories. Life was difficult at first: We were branded lishenets [people stripped of voting rights] and our neighbors were criminals.

I remember when Josef Stalin died we all wore black armbands and my father was in tears. There was this strange ambiguity: On the one hand, we felt a love for our country, but on the other, my family had been robbed of its property.

My first school was an all-girls school. I remember walking past Andrei Tarkovsky’s home on the way there, and stopping to listen to the music playing from his apartment.

Eventually, we moved to a different neighborhood and I was sent to a mixed school. There were no social differences there: The children of train drivers and academics all studied together.

In my second year, a famous all-boys boarding school in Moscow shut down and the students – mostly the sons of military staff and diplomats – were transferred to ours. They swore and behaved like hooligans, but they brought with them an air of freedom and self-expression. They wrote us love letters and fought for our affection.

We felt like women for the first time.

From the eighth to the 11th grade, I had this literature teacher, Irina Bashko, who was an incredibly fascinating woman. She came from a respected family of Kiev academics and was a very independent thinker. She even spent time in a Ukrainian prison for her dissident views. Through her, I was exposed to a range of Russian literature.

I went on to study literary editing at a humanities university. My parents wanted me to study maths, but I didn’t listen.

In my life, I’ve only ever had two loves. I met my first husband when I was about 18. I became acquainted with his brother at an parade, and he invited me to their home for dinner.

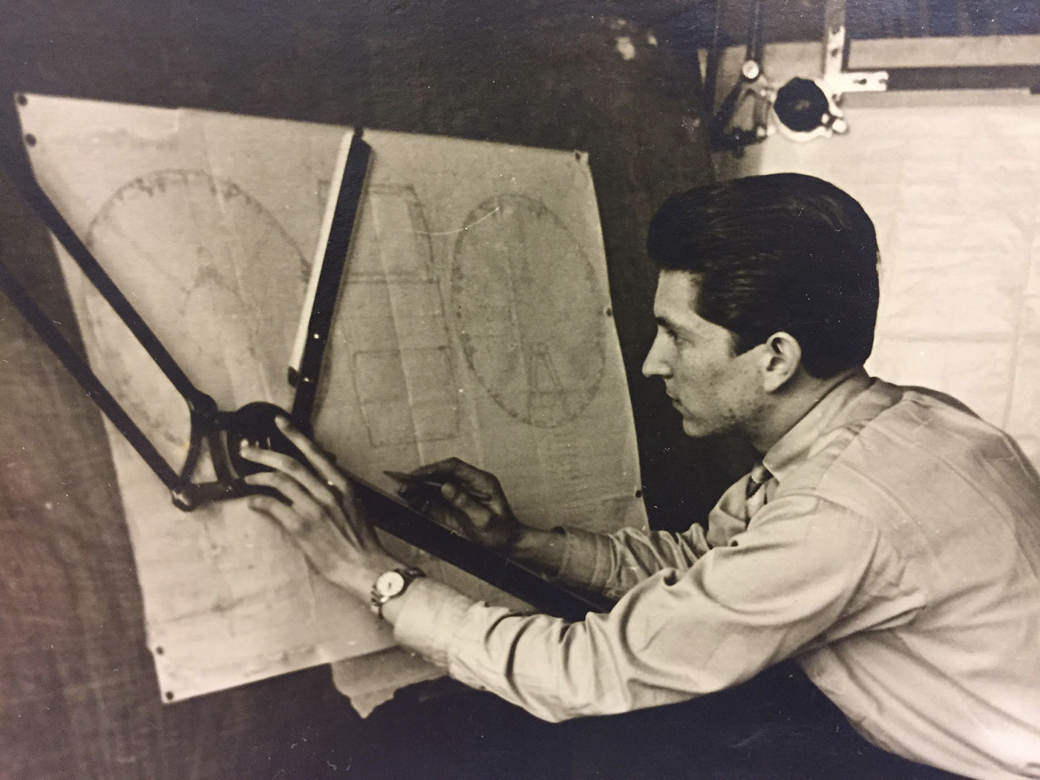

That’s when I first set eyes on him. He was ten years older than I was, but it was instant attraction. He was a wonderful person, and although he came from a simple background, he collected books, was a talented painter and introduced me to wonderful music. He worked as an aerospace engineer at Bauman University.

A year later we married. At 21, we had our first and only daughter, Olga.

My husband always felt that I shouldn’t work as much, and that I should be a stay-at-home mother. He didn’t care for my creative pursuits whatsoever.

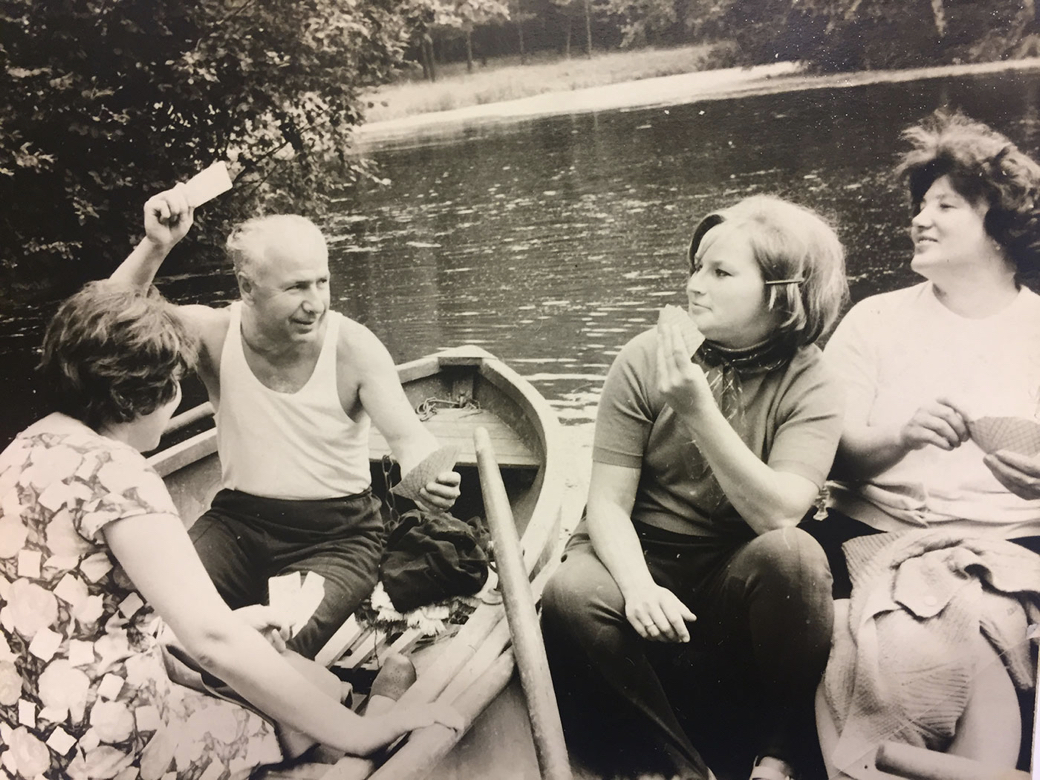

He had a crowd of drinking buddies and spent all of his free time with them. I couldn’t handle the drinking anymore, so when I was 30 I decided to leave him. A few years later he died — Olga was 12 at the time.

Almost ten years later, I met Anatoly while on a walk. He was 11 years younger than I was. Sometime later, he somehow managed to figure out where I lived.

He loved my daughter, and was a good father figure to her. He supported my creative ambitions and would help me write my screenplays. He really wanted to have children together, but I couldn’t do it.

Nobody should have more than one family, it’s not right. We never married. Eventually he left without a trace after a death in his family.

I never stopped working – even when I was seven months pregnant. My relatives would watch my daughter while I was at work as a schoolteacher. The thought of quitting my job never even crossed my mind.

I’ve always been very committed to my work, but deep inside I still feel I’m a person from the East.

I always had this feeling I should have stayed at home and looked after my small tribe.