When I was growing up, the boys and girls in the village all mixed and were friends. There were some separate activities: Girls, for example, were taught how to sew and the boys how to build things.

I didn’t really pay attention to anything but my studies. Then, one day, an older man came to my home to consider me as a potential match.

I was scared. “Wow,” I thought, “Now I’m an adult!” He sort of rated me, like in a film. It was interesting to realize men were now looking at me.

My grandmother would advise me on my suitors, filled me in on their family backgrounds and their personalities. But she never told me about sex. No one spoke about that at home or at school. I got married without knowing what sex was.

I think this is wrong. When a woman reaches the right age, she needs to be taught about sex. But we didn’t understand anything. That’s why our parents wouldn’t let us go to the city. They were worried that the city folk would trick us, because we village girls were so naive.

Parents thought there would be rumors that so and so was wearing make-up or short skirts. Those girls were then given the stink eye in the village.

A year after finishing school, I got married. When I was growing up, girls were married off by their families right after finishing school. Whether we wanted it or not, we didn’t have a choice. Around 18, girls are mature and ready to become mothers.

If my husband had allowed it, I would’ve continued studying. But he couldn’t leave the village because he had to take care of his widowed mother and I had to stay to help him. Here, once you are married, your in-laws become your parents.

We were poor. There were many hardships and financial troubles. We even had problems in bed. Two years after our marriage, we had our first child.

We had a mutual understanding of our roles. He worked at a sovkhoz farm [a state-owned farm in the Soviet Union], while I worked around the home. I looked after the house and disciplined the children.

Together, we built this home from scratch and planted the garden outside.

In some parts of Dagestan they still practice bride kidnapping, but it doesn’t happen here. I remember when I was in Vladikavkaz in Ossetia to complete my exams, I met a woman there who told me she’d been kidnapped.

I was so surprised! She was covered in make-up, had loads of nice purses and clothing. She told me, “Yes, my parents are still looking for me to this day!” I’m completely against it.

A woman is the keeper of the household. She listens to her husband, looks after the home, and disciplines her children.

Raising children is difficult. You need to raise them in a patriotic, spiritual way. It involves teaching someone how to be useful to their community, to their families, and to their future children.

They should not have any bad habits such as smoking or drinking. Here in our village in Dagestan our women don’t drink or smoke at all. It is forbidden, unthinkable. We raise them to work, to be respectful to the elderly, to keep the family together, and to be presentable when in public.

We’ve lost some customs. When I was growing up, a woman wore a red veil over her face during her wedding. Dating before marriage was strictly forbidden; it was very rare for someone to meet their future husband before marrying. It was the parents who decided.

In Soviet times, my grandmother would pray in secret. Sometimes, she would walk around the village during Eid al-Fitr and hand out gifts to our fellow villagers. The next day, my father, who was a member of the Communist Party, would be called in by the local authorities to answer for her actions.

I only go to the mosque on holidays. I could never pray regularly because I didn’t have time for it. I had to take care of the children. Now I’m just not fit enough.

It would be absurd to force somebody to be religious. If you want to pray, pray; if you don’t want to pray, don’t!

I can’t not believe in God. There are many divine things in our lives, from our parents to our motherland.

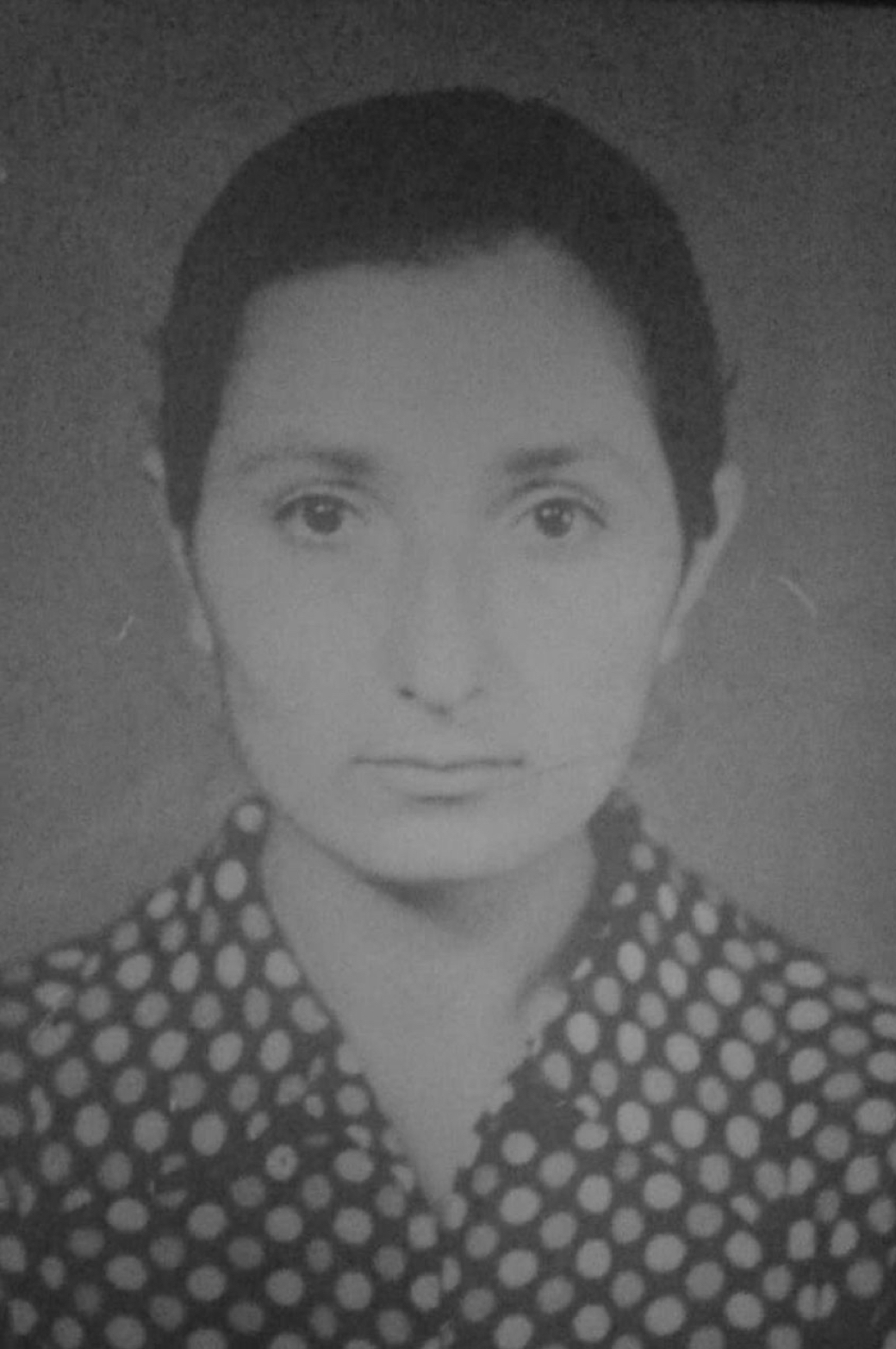

When I was growing up, my grandmother was always the main female authority in the home. Now I have taken her place.

My grandmother was my role model, people respected her. She lost her husband at an early age, but already had six children at the time of his death. She outlived all of them, only my father survived.

She was one of the first students at our village school, when it had just opened. She already had two children by then. There she learned how to read and how to count. What kind eyes she had!

My parents had 8 children: 5 daughters and 3 sons. My grandmother would discipline all of us too. She was a workaholic, good with her hands, and taught us well.

I spent my summers living in the mountains with her, helping her milk the cows and make cheese and butter. In fall we’d come down from the mountains. I was her helper, always next to her.

A woman’s wisdom and kindness come from God and it is passed down from generation to generation.